A Transformative Leader: The Martin Era in Three Acts

Chancellor Harold L. Martin Sr. first joined North Carolina A&T as a student. Later, he returned as a faculty member and academic administrator. When he re-joined A&T once again, it would be for good.

It's an incredible, one-of-a-kind story. We invite you to explore it in the words and images shared in the three chapters below.

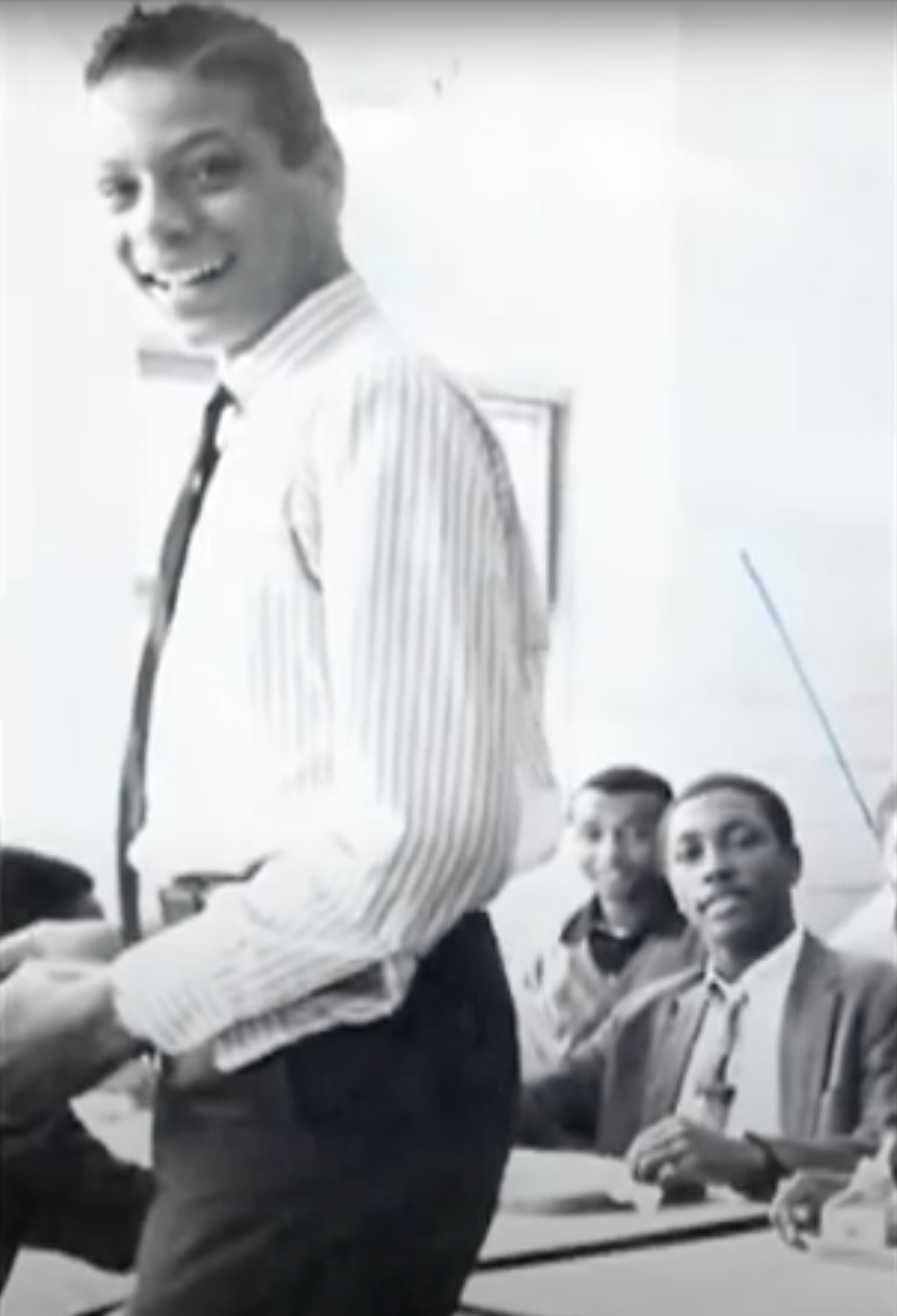

Harold Lee Martin arrived as a student at North Carolina A&T State University in the fall of 1969.

It was familiar territory for the freshman from Winston-Salem: His brother and sister were already Aggies. A standout student and basketball player from Carver High School, Martin showed a serious aptitude for math and related studies. When he outpaced the instructional resources available at all-Black Carver, he was allowed to drive a school bus to a white high school to further his studies. He dreamt of studying engineering and playing Division I basketball at A&T.

A prominent historically Black university (HBCU), A&T was approaching the end of a dynamic decade of change, one that had started in 1960 with the A&T Four sit-ins that captivated the nation and led to sweeping changes in public accommodations laws. Only months before Martin arrived, the campus had erupted in protest over racial discrimination at nearby Dudley High School; the state governor mobilized the largest military movement ever on a U.S. university campus, with National Guardsmen opening fire on an A&T residence hall. One student died of gunshot wounds in what became known as the Greensboro Uprising, and the spring semester ended early.

A&T itself had been designated a “regional university” by the state General Assembly in 1967, resulting in the name it is known by today. In his junior year, Martin would witness A&T becoming a campus of the UNC System.

Martin was captivated by the energy of A&T and the university’s many outstanding students including junior Ronald McNair, just nine years before he was chosen for NASA’s astronaut program. He quickly realized the competition in the classroom and rigor of his studies meant he could excel as an engineering student or as a basketball player, but not both. It was a tough call, but he opted to focus solely on schooling, a decision that led first to his bachelor’s degree and then his master’s, both in electrical engineering.

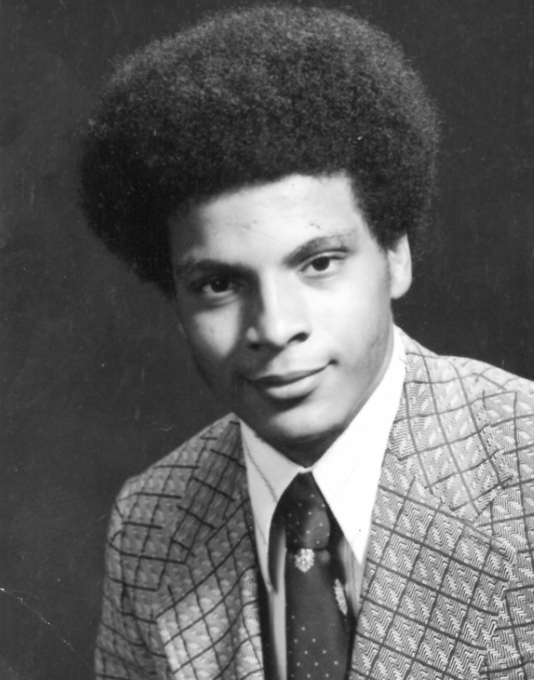

His education wasn’t the only thing on Martin’s mind: Davida Wagner, whom he met and began dating when they were both in high school in Winston-Salem, was also an A&T student, having arrived in Aggieland two years after him. A smart, accomplished undergraduate with an ambition to become an attorney, she captured his heart. They married in 1973, after both had completed their undergraduate degrees. Davida would soon enter law school at Wake Forest University. The foundation was laid for a duo who would later become perhaps the most visible “power couple” in the Piedmont Triad.

Martin might well have continued his graduate education at North Carolina A&T, but state authorities had yet to approve doctoral programs at the university. Off he went, then, to Blacksburg, Virginia, for a Ph.D. in electrical engineering at prestigious Virginia Tech.

Faculty there recognized the intelligence, drive and leadership abilities readily apparent in the young doctoral student. Academic leaders like Wayne Clough (now president emeritus of Georgia Tech), Dean Paul Torgersen (later, Va. Tech’s president), Electrical Engineering Chair Bill Blackwell and academic advisor Gail Gray mentored him, invested in his education and instilled in him an understanding of how to build strong academic programs. Just as importantly, they helped build his confidence as a future leader, allowing him to serve as an instructor for a year as he completed his degree.

Upon graduation in 1980, Martin, now 28, accepted an assistant professor position at his original alma mater in the School of Engineering’s Department of Electrical Engineering. Back in East Greensboro, he began to incorporate in his own work the knowledge gained from his Ph.D. program, embarking on a steady climb up the leadership ladder at A&T.

Within four years, he earned tenure – an uncommonly short progression in higher education. He became remarkably successful as a principal investigator, bringing in substantial, six-figure grants to fuel his research in integrated circuits and high-speed computing. In 1984, he was named chair of the Department of Electrical Engineering, and five years later, dean of Engineering, which had transitioned by that point from school to a college.

As dean, he developed a rigorous strategic plan that called for raising the academic quality of the college by elevating its standards – a move some saw as risky. He won the support of Chancellor Edward B. Fort, who advised him with a smile to “keep your hat and coat handy. If this doesn’t work, they’ll run us both out of town.” But Martin would not allow failure. He led a college-wide push that doubled Engineering’s undergraduate enrollment to 1,700 while also charting significant growth in the entering SAT/ACT scores and GPA of his students. He also more than doubled its graduate student population to 342 students and its research funding to $10.5 million. In his final year as dean, the National Technical Association named the college its College of Engineering of the Year.

There was one more important hill to climb. A&T could not fully develop as a research university without Ph.D. programs, and Martin diligently built the case for doctoral degrees in two of the college’s disciplines: electrical engineering and mechanical engineering. In 1994, the state Board of Governors approved both, and A&T enrolled its first students in each program that fall. Thanks to his leadership, the college was well on its way to a distinction that has defined it for the past three decades: America’s No. 1 producer of Black engineers.

That fall, Fort tapped him to become A&T’s top academic officer, the vice chancellor for Academic Affairs, the position known today as provost. Martin extended the quality-enhancing approach he created for the College of Engineering to A&T’s other schools and colleges, while also sunsetting half of the university’s lowest-producing degree programs. In their place, he launched competitive new undergraduate and graduate programs in disciplines ranging from social work to physics to graphic communications systems.

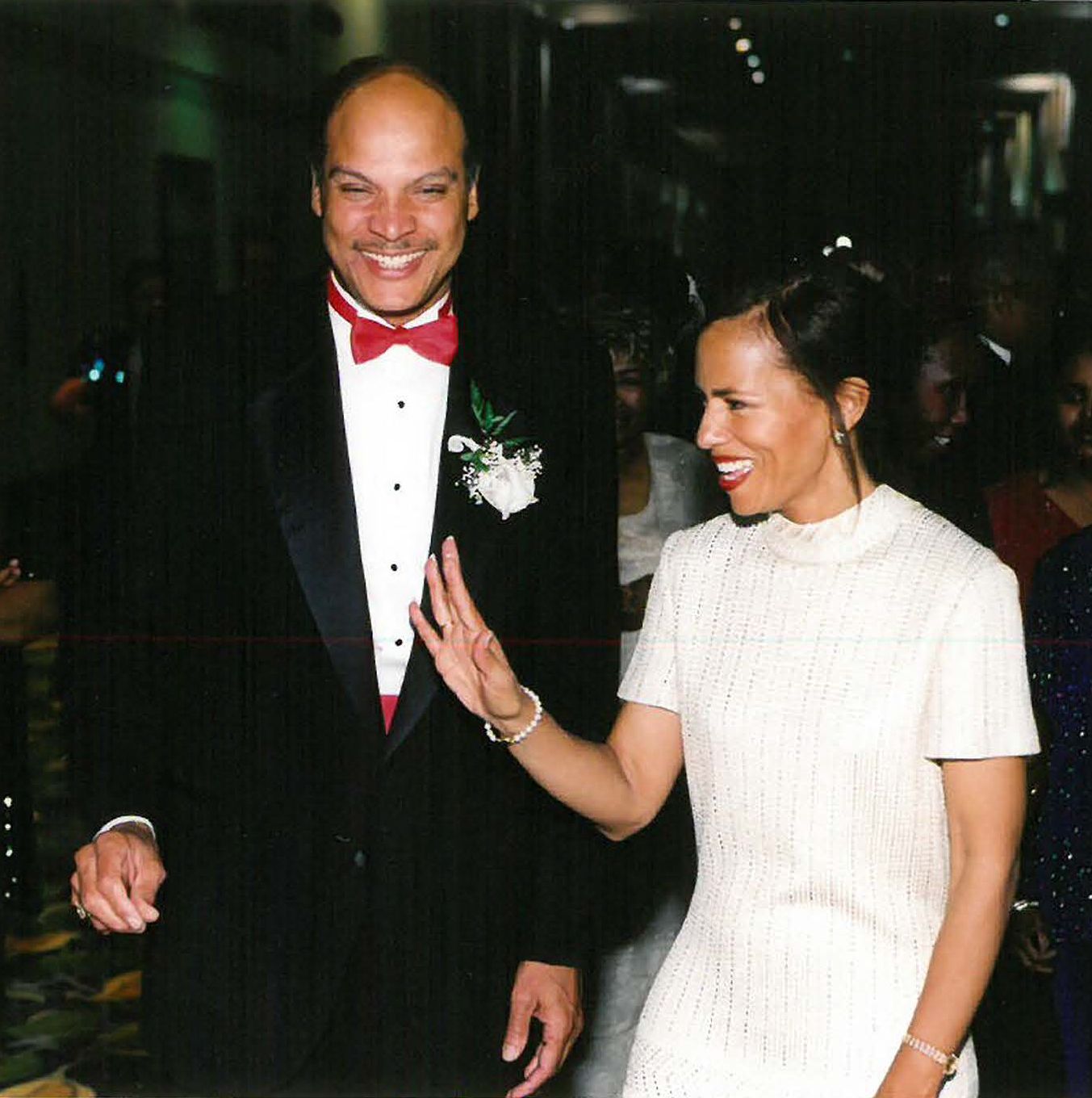

His leadership and success earned fans well beyond Greensboro. In Chapel Hill, UNC System leaders increasingly liked what they saw in A&T’s academic development. Martin’s reputation grew with each new achievement. When the chancellorship of Winston-Salem State University became available in 1999, Martin’s selection was nearly a foregone conclusion. In January 2000, he assumed his first chancellorship at just 48 years old.

The Martin method was just as successful at WSSU as at A&T. To build its quality, he oversaw a restructuring of its academic programs, created a School of Graduate Studies, added seven master’s programs and doubled the university’s enrollment to 5,600 students, elevating a medium-sized HBCU into a nationally recognized campus.

His proven efficacy as an academic leader at two of UNC’s 16 campuses stood out for the system’s prominent new president, Erskine Bowles, formerly President Bill Clinton’s chief of staff. In 2006, Bowles made Martin his No. 2 in leadership, senior vice president for Academic Affairs. His influence and high academic standards now extended over all the system’s universities. Over three years, he not only led academic planning, working closely with chancellors and chief academic officers across the state, but also served as a trusted confidante to Bowles and a senior advisor to the Board of Governors.

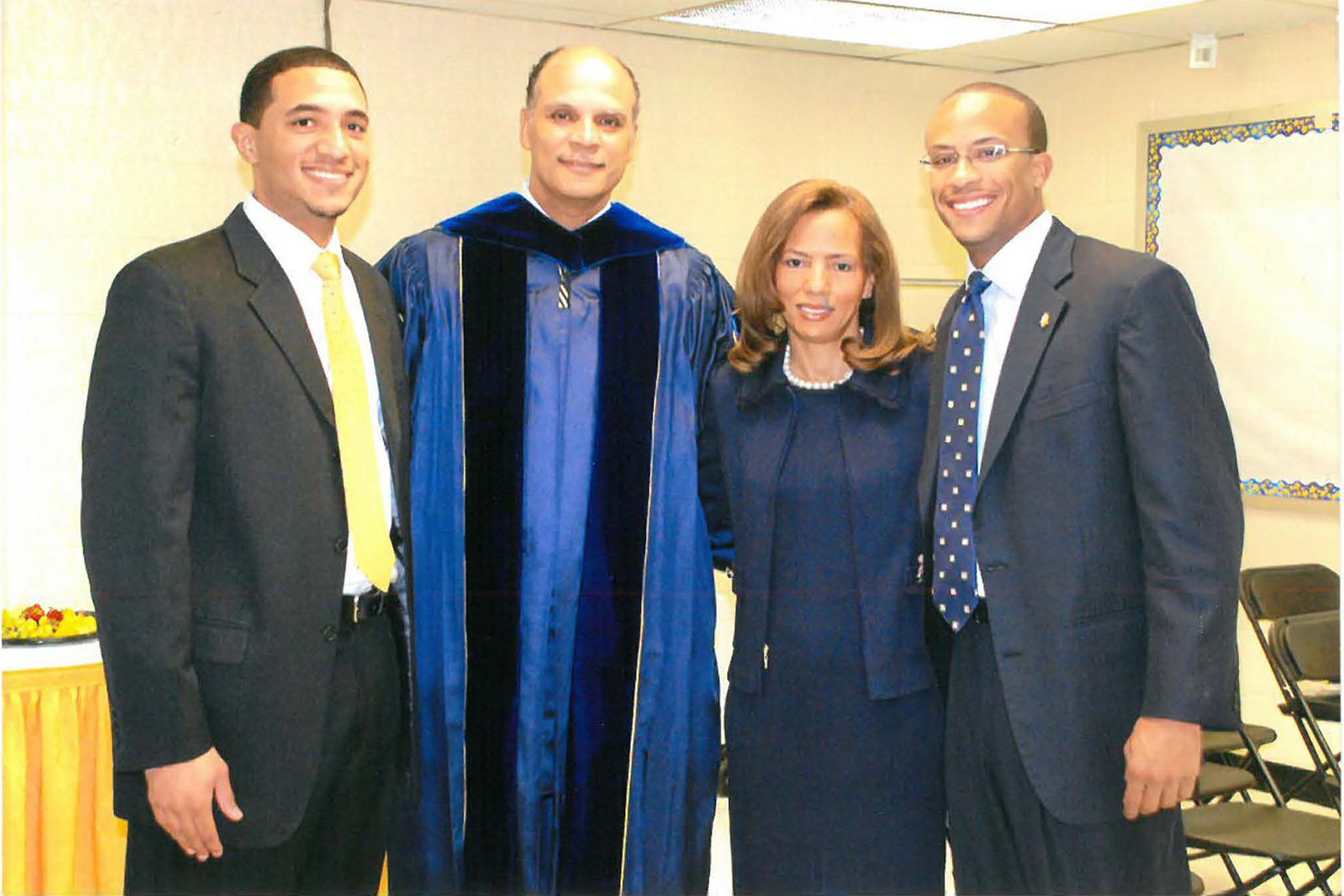

As he scaled the heights of two universities and one of the nation’s most highly regarded university systems, Martin and his wife had grown a family. Sons Harold Jr. and Walter had grown up, gone on to success in college and graduate school and begun their careers. Harold Jr. would later be tapped to serve as interim president of his alma mater, Morehouse College, making him and Chancellor Martin the only father and son simultaneously leading a U.S. college and university.

Now a well-regarded lawyer, Mrs. Martin was well into her tenure as County Attorney for Forsyth County. Having won the job in 1998, she was the first Black woman to hold such a role in North Carolina history, and she would keep it for two decades.

So many accomplishments in one family. But there was more to do. Much more.

In Greensboro, A&T Chancellor Stanley F. Battle had recently announced he would resign at the end of the 2008-09 school year. A search began immediately. By spring, the competitive field had been narrowed to finalists.

For the Board of Governors, the choice was clear: On May 22, Harold Lee Martin Sr. was elected in a unanimous vote to become the 12th chancellor of North Carolina A&T. In accepting, he became the first alumnus to lead the university. Two weeks later, armed with the experience and wisdom of nearly 30 years in senior academic leadership, he began work at A&T on the fourth floor of the Dowdy Administration Building.

Martin had a grand vision for a university in need of a new game plan. But first, he needed buy-in. On June 8, 2009, he spoke to his first gathering of faculty and staff, outlining A&T’s most prominent accomplishments along with opportunities that lay in its future.

And then he threw down the gauntlet.

“Are you ready to compete?” he asked the somewhat startled crowd, and then repeated the question. The response was an enthusiastic, collective “YES.” With that, Martin’s third and most consequential act at A&T was officially underway.

As many new leaders do, Martin faced challenging short-term circumstances. Declining enrollment. An uncertain financial future. A dated academic organization. An athletics department in near free fall. The challenges were big and would require time and money to solve.

Martin was undaunted. His confidence inspired the same across the university. Together, he and his administrative and academic leaders stabilized the enrollment decline and began making headway on finances and athletics.

He presented more detailed and ambitious plans to the A&T Board of Trustees, as well as other key university supporters. Some were unconvinced. “Do you really think we can do this?” asked one leader, he recalls now, with regard to competing successfully against larger and often better-funded peers. Some adopted a wait-and-see attitude as Martin and his leadership team continued to move forward.

Two years after his arrival, Martin introduced the university’s first comprehensive strategic plan under his leadership: “A&T Preeminence 2020: Embracing Our Past, Creating Our Future.” The plan framed new goals and initiatives, as well as unprecedented public outcomes for A&T. It bore the distinct fingerprints of an engineer with a penchant for details and specifics.

Driving the plan became a university-wide commitment. In each division, college, center and office, faculty and staff understood how their work connected to the new document. “Preeminence 2020” became a familiar campus phrase, a clarion call to action.

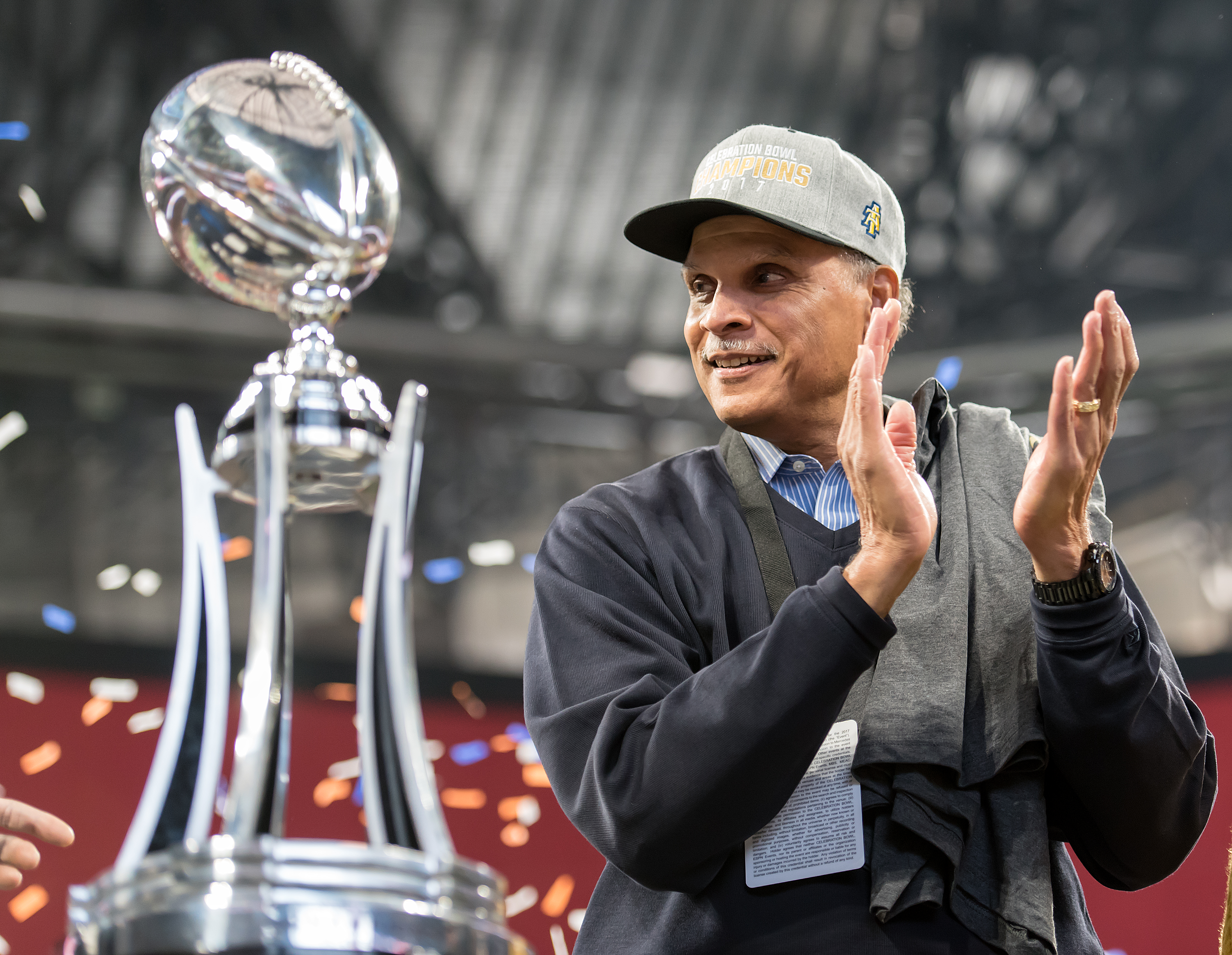

It didn’t take long to show results. In the 2013-14 school year, A&T admitted a bumper crop of new students, setting the stage for a major milestone in fall 2014: A&T became the largest of America’s HBCUs, overtaking Florida A&M for the top post. It is a position the university has held every year in the decade since.

Not only was A&T growing, so was the academic profile of its students. Incoming first-year students had an average GPA of 3.0 in 2009; by 2016, that average had grown to nearly 3.5 (today, it is 3.75.). The idea that A&T could grow and thrive by raising standards rather than relaxing them was being proven in real time.

Other goals within the plan were being realized faster than originally anticipated. In 2015-16, the university seamlessly launched a wholesale reorganization of its academic programs, creating colleges, aligning programs with workplace needs, facilitating retirement of a significant percentage of long-serving faculty and hiring promising new scholars. Similar reorganizations have mired other campuses in conflict, but under Martin, it went off without a hitch. With each success, campus confidence grew. A compelling narrative of success and achievement was taking shape, but A&T under Martin was nowhere near done.

In 2016, A&T stepped into the national spotlight, hosting a televised town hall with President Barack Obama, carried on ESPN. As part of its own coverage of the hour-long event, the network posted a feature about A&T that demanded attention, particularly from readers who didn’t know much about the university. “How Did North Carolina A&T Become the Country’s Leading Producer of Black Engineers?” the story’s incredulous headline asked.

The answers to that question were compelling and timely for a nation in dire need of STEM graduates as well as diversity in STEM professions. A&T built on its notoriety with the launch of the Chancellor's Speaker Series, which welcomed Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg and Shark Tank entrepreneur Daymond John as its firs two guests in spring 2017. The following fall, A&T admitted its largest entering class, pushing enrollment to just under 12,000.

Others began taking notice. In early 2018, nine years into the Martin era, The Atlanta Journal-Constitution published an extensive examination of HBCUs. The sprawling project included numerous stories, including one devoted entirely to A&T’s development under Martin. It read, in part, “Over the last decade, North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University – known for its engineering programs and a legacy that includes ‘The Greensboro Four,’ Jesse Jackson and Ronald McNair – has moved quietly and resolutely toward its goal of becoming the best Black college in the country. ‘This is truly an exciting time to be an Aggie,’ said Chancellor Harold L. Martin Sr.”

That fall, the university completed its largest construction project under Martin: The 150,000-square-foot Student Center, funded entirely with student fees. A modern and colorful three-story structure with a spacious atrium notabale for its striking, gently sloping yellow staircase, it immediately became the heart of the campus. Martin loved to stop by and walk its spacious commons, engaging a never-ending string of students in conversation about their studies and life on campus.

Martin responded to the university’s growing success and notoriety with a refreshed strategic plan, “A&T Preeminence: Taking the Momentum to 2023,” that raised the bar in multiple areas – research funding, private support, community engagement, development of the campus intellectual climate and more. Having achieved so much under Preeminence 2020, faculty and staff readily embraced the new plan.

A&T’s very public and transparent pursuit of strategic goals not only drove new success, but also helped build external faith in the university’s development – a fact vividly documented in a phone call Martin received in fall 2020. The caller was a senior representative of philanthropist MacKenzie Scott, who had made news in recent years for her commitment to give away most of her multi-billion dollar wealth. Scott wanted to make a substantial gift to the university, the caller said. A gift of $45 million, the largest single gift donation received by A&T.

In dialogue over the following weeks, terms of the donation were finalized. One of the most fascinating was Scott’s answer to whether A&T needed to provide a plan for how it intended to use the donation.

Not necessary, was the response. Scott had studied A&T under Martin’s leadership and was confident the university would use the funds to their best possible advantage. The gift helped propel The Campaign for North Carolina A&T fund drive well past its original goal of $85 million to $181.4 million in 2020, making it the most successful capital campaign ever for a public HBCU.

Despite the challenges of the COVID-19 pandemic, A&T's continued ascent over the past four years under Martin has been no less than breathtaking. In February 2022, the university drew attention across the state as it opened a sleek, glass-encased four-story engineering edifice: The Harold L. Martin Sr. Engineering Research and Innovation Complex. N.C. Gov. Roy Cooper and a throng of government and business leaders, media and the extended Martin family were on hand for the grand opening of the $90 million cutting-edge complex and to pay tribute to the building's namesake.

In early 2023, the university rolled out its final strategic plan under Martin. That fall, the university marked its 10th consecutive year as America's largest HBCU, with a student body of 13,885 and plans to grow to 15,500.

Now the longest currently serving HBCU leader in America, as well as the chancellor with the longest current tenure in the UNC System, Martin had logged more than 14 years as A&T's leader - nearly three times the average tenure for a university CEO. Mrs. Martin had retired from her accomplished legal career five years earlier and Chancellor Martin was closing in on his 72nd birthday. It was time.

At the Sept. 22, 2023, meeting of the A&T Board of Trustees, with Mrs. Martin by his side, Chancellor Martin announced he would retire at the end of the school year. It was an emotional moment for everyone in the room. Martin made clear, though, that he had a final year left, and did not plan to spend it on a farewell tour. There was still so much he wanted to do.

In May 2024, Martin will preside over his final commencement as A&T chancellor. He and Mrs. Martin will also be honored as members of the Golden Aggie Class of 1974, a poetic ending to his tenure. He leaves behind an A&T standing on an extraordinarily sound foundation, in the midst of taking on bold new challenges and continuing its upward ascent thanks to his transformative leadership.

Those who know him fully expect Martin to be working as hard toward A&T's success as he did as a student, as a faculty member, dean and vice chancellor, and as he has done as the university's leader since the start of his final act at A&T in 2009.

Chancellor Martin has long been fond of a familiar phrase that he has used often over the past 15 years: "At A&T, we are always better than yesterday, but never as good as we will be tomorrow." That sentiment has been distilled into A&T's tagline today, one that will be long remembered as characteristic of the Martin era in Aggieland:

Always doing. Never done.